The Bermuda Triangle

On our addiction to hyperbole and sensationalism

Surely, if you’ve been around a few decades, you’ve heard the lore about the Bermuda Triangle. Like fables of people disappearing into quicksand, stories claiming that there is a mysterious section of the Atlantic where various planes and ships have disappeared into the mist have been seared into our collective consciousness.

Interestingly, we don’t hear as much about unusual disappearances, or stories about mysterious happenings taking the lives of sailors or pilots there in more recent years. Why is that?

Well, first, let’s go back to when this all started.

I assume you already know that Christopher Columbus “discovered” America by landing in the Bahamas on October 12, 1492. In the following centuries, this part of the Atlantic became known for being a haven for pirates and merchants. So, for the western world, this part of the ocean was unexplored for millennia, and then suddenly became a significantly traveled path between the old world and the new.

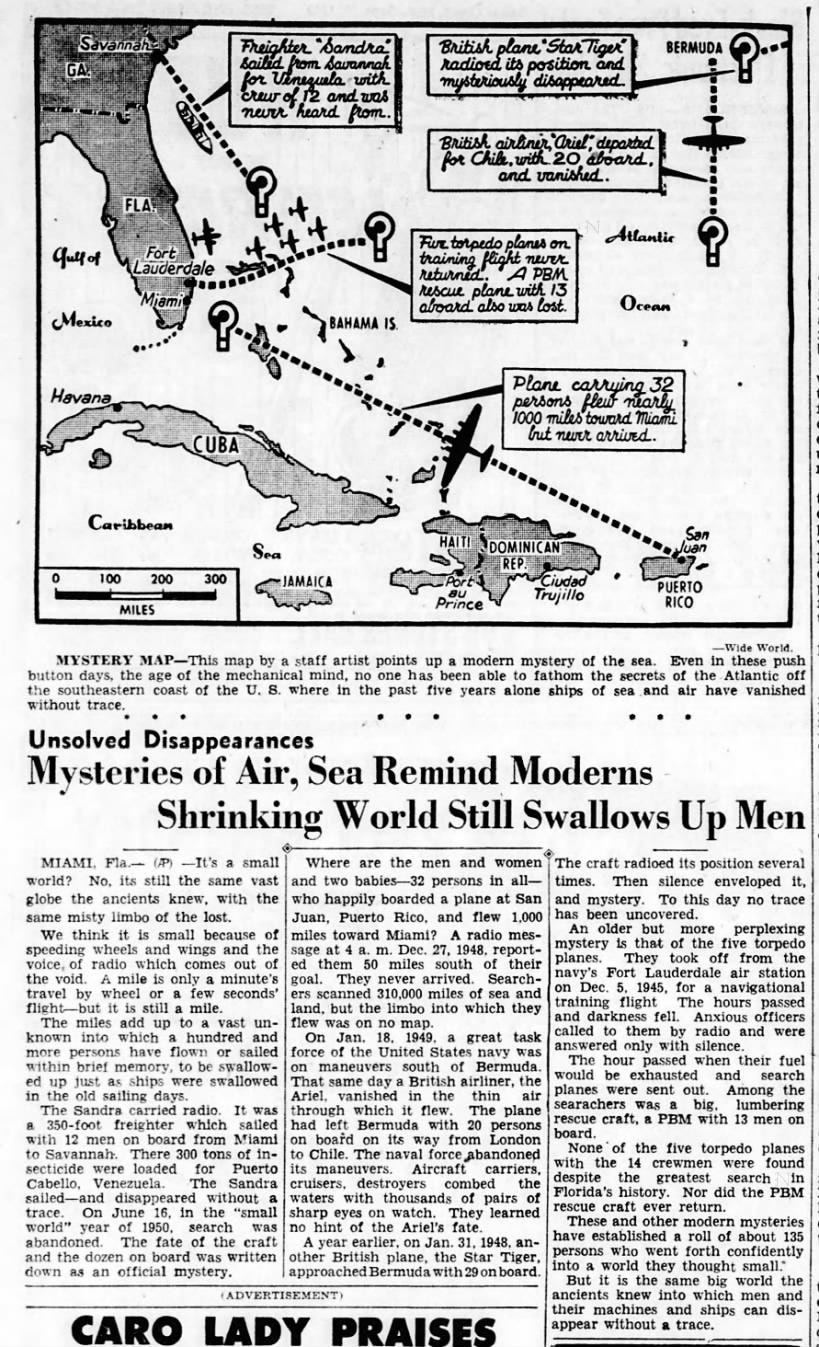

On September 17, 1950, only five years after the end of the second world war, Edward Van Winkle Jones of the Miami Herald published a story claiming that a large number of tragedies had occurred in locations off the eastern coast of the United States. Here’s the graphic accompanying that article:

Two years later, George X. Sand published an article titled “Sea Mystery at Our Back Door” that laid out the specific area of calamities as occurring in a triangular area between Bermuda, Puerto Rico, and southern Florida (see below).

Sand described the loss of several planes and ships since World War II, including the disappearance of the steamer Sandra, the loss of Flight 19, containing five US Navy torpedo bombers on a training mission, and the January 1948 disappearance of a British South American passenger airplane, as well as others.

In the April 1962 issue of The American Legion Magazine, Allan W. Eckert wrote that the flight leader on Flight 19 had been heard saying, "We cannot be sure of any direction ... everything is wrong ... strange ... the ocean doesn't look as it should."

In February 1964, Vincent Gaddis wrote an article called "The Deadly Bermuda Triangle" in Argosy saying Flight 19 and other disappearances were part of a pattern of strange events in the region, dating back to at least 1840. The next year, Gaddis expanded this article into a book, Invisible Horizons.

As time went on, further stories about the Bermuda Triangle became urban lore, appearing in numerous songs and movies, further cementing its status as “common knowledge”. In a manner of speaking, we were all off to the races, bolstering this urban myth into popular culture for decades. In the 21st century, we might say that this type of story became “viral”.

One might compare this urban legend with other popular myths, including those about vampires and zombies. Those concepts become fodder for a new generation of writers and publicists anxious to create a modern audience for these tales. And as a culture, we eat them up.

But seldom do we take a moment to thoughtfully consider the validity behind these various myths. What is the actual truth?

“There is no evidence that mysterious disappearances occur with any greater frequency in the Bermuda Triangle than in any other large, well-traveled area of the ocean,” - US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association (NOAA)

In 1975, Larry Kusche published The Bermuda Triangle Mystery: Solved (1975), which argued that many claims of prior writers were exaggerated, dubious or unverifiable. In fact, Kusche concluded:

· The number of ships and aircraft reported missing in the area was not significantly greater, proportionally speaking, than in any other part of the ocean.

· In an area frequented by tropical cyclones, the number of disappearances that did occur were, for the most part, neither disproportionate, unlikely, nor mysterious.

· Writers often failed to mention such storms and sometimes even represented the disappearance as having happened in calm conditions when meteorological records clearly contradict this.

· The numbers themselves had been exaggerated by sloppy research. A boat's disappearance, for example, would be reported, but its eventual return to port may not have been.

· Some alleged disappearances were, in reality, not mysterious. One plane believed to have disappeared in 1937 had, in fact, crashed off Daytona Beach, Florida, in front of hundreds of witnesses.

· The legend of the Bermuda Triangle is a manufactured mystery, perpetuated by writers who either purposely or unknowingly made use of misconceptions, faulty reasoning, and sensationalism.

“There is no evidence that mysterious disappearances occur with any greater frequency in the Bermuda Triangle than in any other large, well-traveled area of the ocean,” said the United States’ National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association (NOAA) in 2010. In 2017, Australian scientist Karl Kruszelnicki told The Independent that the sheer volume of traffic—in a tricky area to navigate—shows “the number [of ships and planes] that go missing in the Bermuda Triangle is the same as anywhere in the world on a percentage basis.” Lloyds of London, the major insurer, has concluded the same.

“The U.S. Navy and U.S. Coast Guard contend that there are no supernatural explanations for disasters at sea,” NOAA continued. “Their experience suggests that the combined forces of nature and human fallibility outdo even the most incredulous science fiction.”

And yet, fifty years later, if you were to mention the Bermuda Triangle, there’s still a certain public fear that there is a disturbing supernatural presence in that part of the ocean that mysteriously swallows ships and airplanes. Despite no evidence of having more accidents or disappearances occurring there than in any other similar locations.

That is the power of the kind of hyperbole that has fueled journalism and our collective appetite for conspiracy theories throughout human history. We seem to love a good unexplained melodrama. As the world becomes more and more complicated, instead of trusting in established fact, humans seem to fall prey to magical solutions as much, or more than ever.

The irony today seems to be that in our polarized culture, where we’re now fed more of whatever we like through sophisticated algorithms that filter more of what we “believe” and less of what we don’t, thus reinforcing our most untested, sensational sources of knowledge and making us, well, stupider.

People tend to fear what we don’t understand. We also don’t seem to be particularly successful at weeding out verifiable fact from sensationalism. The latter, of course, is an editorial tactic where events and topics are selected and worded to excite the greatest number of readers. In modern vernacular, we call it “click bait.”

And now, here we are. In a modern-day Bermuda Triangle of disinformation, where so many poorly informed people feel strongly about positions they know little to nothing about. It’s so easy to believe in supernatural or magical explanations for things we don’t understand, because it feeds a part of us that wants to pull out the popcorn and watch the melodrama, much like our appetite for documentaries about cults or psychopaths.

There are innumerable Bermuda Triangles out there, but if we want to truly understand what’s happening, we have to go beyond the headlines, beyond our echo chamber, beyond the often ill-informed opinions of our communities, and do our own independent research. Question our own assumptions and consider positions that differ from our own.

Otherwise, we’ll find ourselves believing nonsense peddled by people who pretend to have our best interests, but truly only want to have us believing in another Bermuda Triangle.